|

A supplement to the |

|

Website and eBook by Angela and Cyril J Wood |

So You Want To Go Canal Cruising

An Introduction To Canal Cruising

|

A supplement to the |

|

Website and eBook by Angela and Cyril J Wood |

|

|

|

So You Want To Go Canal Cruising

I am frequently asked how get started in canal cruising. Accordingly, this section of the Canalscape website is aimed at prospective boaters wanting to know more about this fascinating and rewarding pastime. It provides an insight into canal cruising, how to get started, discusses canal features, basic navigation principals and etiquette, how and where to hire a boat from as well as the different types of canal craft and how to go about purchasing one and the pitfalls that can be experienced in buying. It also discusses the basic maintenance a boat requires. There are hyperlinks to various companies and other websites that provide information that will be of use and interest in the Useful Links Section at the end of this section of the Canalscape website.

Our canals and inland waterways are (with some notable exceptions) a legacy left to us by the Industrial Revolution. During that period they were the primary means of transporting raw materials and finished articles in the same way that the later railways and today's motorways do, The infrastructure is, in many cases, of listed status and some are Scheduled Ancient Monuments or even UNESCO World Heritage Sites. This, coupled with the relaxed pace of life makes canal cruising a refreshing interlude from the pace and pressures of everyday life and an ideal holiday destination for those not content (or able) to sit on a sun lounger soaking up ultra-violet radiation from the sun or just want something different. It is gratifying to note that our canals and inland waterways receive visitors from all over the world, such is their attraction.

The impressive Pontcysyllte Aqueduct on the Llangollen Canal is a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Before considering hiring a boat for a holiday it is advisable to take a "test drive" on a day boat to see if it is conducive to all the members of the family of those involved. Canal cruising is not for everyone and there would be nothing worse than spending hundreds if not thousands of pounds on a hire boat holiday if some members of the family discover after the first day that they hate it. This does happen and I have spoken to many people who have hired a boat for a week or a fortnight only to discover that the unpredictable nature of the weather or slow pace of life on the canals does not meet their expectations.

Rambling Thorn is a typical day hire boat from Thorn Marine at Stockton Heath on the Bridgewater Canal in Cheshire

A day boat can be hired for around £150 per day and they usually can accommodate about ten people. If the cost of the hire is split between these ten people it equates to around £15 each. Where else can you have a nice relaxing day in the country for that amount? Day hire routes are usually to cruise in the morning towards a particular destination, have lunch and then retrace your steps (or wake) to where the boat was hired from. Some boats have basic cooking facilities on them but it is more usual to cruise to a particular pub for lunch before turning around for the return trip. The routes are usually not too difficult and have a minimal amount of locks, tunnels, lift/swing bridges or other navigational features. But a word of warning... canal cruising can be really addictive to those who enjoy it.

A group of hirers enjoying a day out on the Bridgewater Canal

Once the "test drive" has been successful and left the prospective boater wanting more, the next step is to hire a boat for a longer period of time. If this is the case then a visit to a hire cruiser base should be planned to view the boats and get an idea of the layout, size and type of boat you might like to hire. Dealing with the size of the boat first... this normally reflects the number of people the boat is to accommodate The number of beds, bunks or, as they are more usually referred to, berths these boats can accommodate ranges from two to twelve. Obviously, the more berths the longer and more expensive the boat is to hire. There is no need to hire an eight berth boat of there are only two of you. The longer boats are usually less manoeuvrable and more difficult to handle.

An idyllic scene of a typical hire boat leaving a lock on the Llangollen Canal

Also, most canal locks are seventy two feet long and the maximum boat length they can accommodate is seventy feet. However, there are some canals whose locks are sixty two feet in length so can only accommodate sixty foot long boats with care and a better length for canals that possess locks of this length is fifty eight feet, so it is best to check with the hire cruiser staff that the boat you ultimately hire is suitable for the route planned to cruise. More information regarding locks is given in the Navigation Section of this webpage. Another thing to consider is the layout of the boat. If there are two groups of adults that require their own privacy, open plan boats are best avoided. The double beds need to be separated by either a bulkhead (partition) or parts of the boat such as the toilet/shower compartment. This avoids any embarrassment having to pass people sleeping if the toilet needs to be used during the night.

Talking of toilets, a recent young visitor to our boat asked "Where does all the wee and poo go?" There are two basic types of toilet on a boat... the cassette toilet where all waste goes into a removable portable tank or cassette that is emptied at various locations along the canal known as Sanitary Stations. The second type is known as a pump-out toilet where the waste goes into a fixed steel tank hidden from view that is pumped out at boat chandlers or marinas. In cassette-type toilets an additive (known as Blue Loo Liquid or Elsan Fluid) is used in the cassette to prevent unwanted odours. A less common type of toilet is the composting toilet. This stores the untreated sewage in a composting tank where the solids are composted by bacteria or fungi. Sawdust, coconut fibre or peat moss is added after use to stimulate the composting process. The previously mentioned Sanitary Stations usually provide other facilities such as a water point where the boat's water tank can be filled up with a hose pipe, rubbish bins or skips where your rubbish can be deposited. They may also possess showers and even, in some cases, laundry facilities and a do-it-yourself toilet pump-out. Access to these facilities usually requires the use of a "Watermate" key (also known as a BWB key).

Emptying a toilet cassette at a sanitary station

Filling the water tank from a canalside tap

The cold water is heated by the engine via a heat exchanger known as a calorifier or gas fuelled water heater. Other utilities on the boat include gas and electricity. Gas is stored in gas bottles located in lockers that are vented to the atmosphere. Electricity was almost exclusively 12 volt dc as on a car and generated by the boat's engine and increasingly supplemented by solar panels mounted on the roof. The resulting electricity is then stored in large batteries. It is the usual practice to have several "leisure" batteries to power the boat's lighting and internal systems with a separate battery for the engine. In recent years mains electricity is found more and more on boats. Mains electricity is obtained either from a land-line hook-up, a 240 volt ac generator (sometimes powered by the boat's engine) or from the 12 volt storage batteries and converted to 240 volts ac by a unit known as an inverter. Historically heating and cooking was once achieved using a solid fuel stove and range but gas cookers are now is the usual way of cooking and Diesel fuelled central heating is becoming more and more popular. Fuel for the boat's engine (and possibly heating) and gas for cooking (as well as heating on older boats) and coal for the solid fuel stove (if fitted) is either obtained from canalside boat supply shops and marinas or in some cases delivered to the boat from a floating fuel/gas/coal station... usually an ex-working narrowboat.

The outside layout of the boat should also be considered. If there are a few people in the party wanting to socialise on the rear deck it is best to avoid boats with a "traditional" stern as there is only enough room for the steerer and possibly one other. A more sensible alternative is the "cruiser" stern which has a large aft deck (usually with the engine beneath) that can accommodate a small folding table and a couple of folding chairs. Some boats have integral aft deck seating or even what is known as a "semi-trad" stern which has the lines of a traditional boat but the functionality of a cruiser stern.

A narrowboat with a spacious cruiser stern...

...a more cramped but better looking traditional stern...

...and the compromise of looks and spaciousness is the semi-trad stern

These points might seem common sense but, when viewing a potential hire boat (or a boat to purchase) they can easily be overlooked. Most hire boats have a large foredeck where one can relax with a glass of wine or other beverage as the boat passes along our picturesque canals and inland waterways or when tied-up at the end of a day's cruising.

Spacious fore deck

General: Our canals and inland waterways possess many features that add to their charm but also require a little basic knowledge to ensure a trouble free cruise. The basic rule of the road (or waterway) is the side of the waterway that you keep to when passing other craft. It is the opposite to that of English roads... that is you keep to the right with the boat you are passing on the left. The theoretical speed limit on most (but not all) canals is four miles per hour. In practice it is not always possible (or desirable) to keep to this speed. If the canal is shallow and the throttle is opened to make the boat go faster all that will happen is that the propeller will suck the stern of the boat closer to the canal bed and, in addition to actually slowing the boat down will produce a greater wash that will erode the canal banks. This is a hydrodynamic principle known as squatting. The solution is to lower the engine revs and you will go faster and have greater steering control of the boat. It is also worth slowing down a little as the sides of the canal are usually shallow due to the saucer profile of the canal bed. It is also a common courtesy to slow right down when passing moored craft and fishermen. The slowing down manoeuvre is not instant due to the inertia (momentum) of the boat. Depending upon the boat's speed it can take quite a few boat lengths for the boat to slow down so it is best to slow down well in advance allowing the boat's wash to dissipate as well. The heavier a boat is, the greater its mass and hence it requires a greater distance to slow down... a fact that many boaters seem to forget! At certain times of the year, especially autumn when there are a lot of fallen leaves in the water, the boat will slow down for no apparent reason. This is most probably due to a build-up of leaves or other water-born debris disrupting the flow of water through the swim (the pointed bit under the water leading to the propeller) and hence to the propeller. A quick burst of reverse will usually clear the problem. Regarding fishermen, keep to the centre of the channel when passing them. Sometimes the fishermen will tell the steerer to go to a particular side of the waterway in order to prevent the boat's propeller stirring-up the water where they are fishing. This is not always a good idea as the fisherman may not be aware of submerged obstructions or shallows that the boat may strike. If in doubt... stay in the centre.

Navigating through a fishing match

Cruising through leaves in autumn

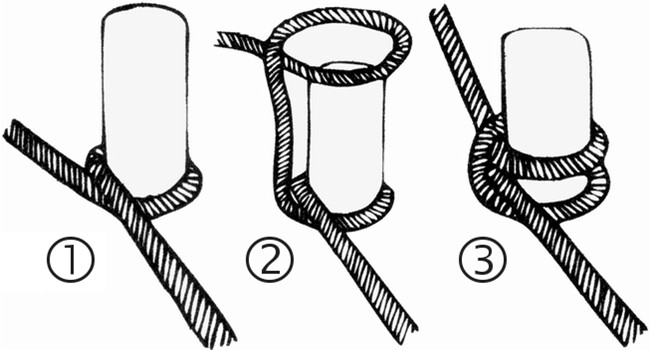

On rivers the speed limit is usually greater for going downstream than it is going upstream due to the speed being measured against the passage of water on the hull and not the river bank. Different rivers have differing speed limits so it is always advisable to check navigation guides and local notice boards. There are an increasing number of official moorings on the inland waterways which possess mooring bollards to tie the boat up to. But if a mooring such as this is not available there are a few points to remember. Mooring stakes are provided to tie the boat's ropes to. Do not stretch the mooring ropes across the towpath as they could cause injury to pedestrians or cyclists. Do not moor in bridge holes, on aqueducts, in narrow stretches, cuttings or embankments, in or adjacent to locks, opposite winding holes (wide sections of canal where boats can turn around), on the off-side of the canal (usually private land) or any other place where warning signs prohibit mooring. The ropes are usually tied by various knots and the boater will usually have their own favourite way of tying them. I prefer to use a clove-hitch tied directly to a bollard or looped through the eye of a mooring pin and tied onto the boat's cleats (where the ropes are secured to) as it is quick, secure and easy to untie.

Basic instructions for tying a clove hitch rope knot onto a mooring bollard

Fixed Bridges: There are many types of bridges on our waterways but the most common is the hump-backed bridge. If you are on a narrow canal and another boat is seen approaching the bridge in the opposite direction it is basic manners to slow down or even stop to allow them to pass through the bridge before you do. Ignorant boaters may try to beat you to the bridge even though you were there first. A tip is to keep an eye on the wash from the other boat. If it increases they have opened the throttle to try and get to the bridge first risking a collision. If the bridge is situated on a blind bend it is best to sound the horn to let any unseen craft approaching in the opposite direction that you are there. Slow right down just in case your horn warning is ignored and be prepared to stop and reverse to allow them passage. Keep an eye on the water on the opposite side of the bridge for the wash of approaching boats. Some canals have a slight current on them, especially if near to a lock that is being emptied. his can cause the boat to slow down of its own accord whilst passing through the bridge hole or narrows. One is tempted to open the throttle and speed up in these circumstances. This can cause the boat to become uncontrollable in certain circumstances and of there is a boat waiting on the other side of the bridge can even risk a collision. It is far better to leave the throttle where it is and let the boat's momentum or inertia carry it through the bridge. This not as much of a problem on wider canals and, depending upon the width of the channel, two boats may even be able to pass each other whilst going through the bridge. Most motorway bridges are like small tunnels. Some are quite wide possessing the same width as the canal whilst others are narrow and, as with an ordinary bridge, best to hang back if there is a boat approaching.

A narrow hump-backed bridge

Movable Bridges: Some canals feature movable bridges. They can be of the lifting (bascule) type and some may swing. Both types may be operated manually requiring the operator to unlock and push wind the bridge's mechanism. Some possess varying amounts of automation that vary from dropping road barriers, operating warning lights and audible signals to swinging or lifting the bridge. There are always instructions on the control panels of automated bridges that will require a Canal and River Trust "Watermate" key to allow operation. These keys have other uses that will be discussed later on.

A Canal and River Trust "Watermate" or BWB key

There are a couple of unusual vertical lift bridges on the waterways network such as the Leamington Lift Bridge on the Glasgow and Edinburgh Union Canal in Scotland and the Turnbridge (or Locomotive) Bridge on the Huddersfield Narrow Canal in Yorkshire that require specific instructions that are given on the control panels for these bridges.

A typical lift bridge on the Caldon Canal

An electrically operated swing bridge on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal

Aqueducts: The aqueduct is another type of bridge that takes the canal over a valley, road, railway or other depression in the way of the canal's route. On some canals (notably the Bridgewater Canal) the smaller aqueducts across roads are called underbridges which is basically what they are. Aqueducts vary from the smallest culvert carrying the canal a metre or so across a stream or small river to examples such as the Chirk and Pontcysyllte Aqueducts which span river valleys many tens of metres high and hundreds of metres in length. Most aqueducts are only wide enough for one boat to cross and in the height of the boating season queues will form on the more popular canals at these locations. Most aqueducts are basically a stone or brick trough only slightly wider than the maximum beam or width of boats that the canal can accommodate. This can cause problems due to constriction of the water channel or build-up of water in front of craft crossing them which, in effect, slows them down. However, when Thomas Telford built the mighty Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, he was aware of this problem and cantilevered the towpath across a wider water channel thus allowing water to flow around the side of craft crossing the aqueduct. This principle has been copied by subsequent canal engineers although budget constraints didn't always allow implementation of Telford's design. One unusual design is the Barton Swing Aqueduct which carries the Leigh Branch of the Bridgewater Canal across the Manchester Ship Canal at Barton Near Manchester and swings to allow tall-masted vessels to pass along the Manchester Ship Canal below.

Lumbrook Underbridge on the Bridgewater Canal

Tunnels: Brief mention was made earlier of tunnels. They are, in essence, long bridges that vary in length from a few tens of metres to, in some cases, a few kilometres. Some are wide enough to allow two boats to pass each other but generally tunnels are only wide enough to accommodate boats travelling in one direction. Many of these tunnels, especially those that have are not straight and the other end cannot be seen, have a timetable to control passage, others you can enter at any time provided that there aren't craft already in them, Before entering keep a lookout for approaching headlights or horns being sounded.

Before entering a tunnel keep a look-out for approaching headlights

There is an increasing amount of boats that possess navigation lights. They usually consist of a red light to port (left) and a green light to starboard (right) but some boats may have a white light at low level on their stern, Sometimes they can be mistaken for a headlight but if in doubt do not enter if the light is visible. Whilst waiting to enter a tunnel check your headlight and keep it on so that on-coming craft know that there is a boat waiting to enter. Many boaters will close one eye prior to entering the tunnel so that when the darkness of the tunnel is entered the eyes do not have to accustom themselves to the lower light levels due to night vision having already been implemented in one eye. Once the tunnel is clear and the boat is in the tunnel sound one long blast of the horn just in case there are un-powered craft that do not have lights in the tunnel.

Inside Britain's longest canal tunnel... Standedge Tunnel on the Huddersfield narrow Canal

If you go through a tunnel slowly you will most probably be correcting the steering continually. If you go through a bit faster there is an equal build-up of water pressure on either side of the boat's hull that will help to keep it in the centre of the channel and require less course corrections by the tiller or rudder. This is a hydrodynamic principal known as the "Canal Effect". Not all tunnels are straight and care has to be taken whilst negotiating these slight bends. Don't forget, if you go too slowly there will be less water passing over the boat's rudder and steering will be affected or non-existent. Most tunnels have ventilator shafts and care must be taken when passing beneath them as quite often water will be dripping from them especially if it is or has been raining. There are usually notice boards at either end of the tunnel informing boaters if a timetable is in operation, to extinguish all naked flames and other basic health and safety information that must be adhered to.

Inside Preston Brook Tunnel...

...and the less spacious Leek Tunnel on the Caldon Canal

Locks: Lastly are locks. These constructions are built to overcome levels in the canal's route in the same way that a person will go up and down stairs and were first used by the Chinese on the Grand Canal in Medieval China around 1000AD. There are a few different variations of the basic design but they are all operated in the same way. A lock chamber is best described as a bath with taps at one end to let water in and a plughole at the other end to let water out. Instead of taps and plugholes the water is controlled by paddles or sluices. They are basically sliding panels in either the lock gate or side of the lock chamber which are raised or swivelled to expose an opening allowing water to either run into or out of the lock chamber. Locks can be either narrow or side and are usually the deciding factor as to whether a canal is broad allowing passage of broader beam craft such as barges or narrow which can only accommodate narrowboats or narrow beam cruisers. On river navigations and ship canals the locks can be much larger to accommodate sea-going vessels. Sometimes locks are grouped in flights of multiple locks especially when the terrain is hilly or when the canal is of the later "cut and fill" variety where it is more convenient to group the locks together.

A typical narrow lock...

...two narrowboats sharing boats sharing a broad lock...

...and a much larger river lock. This example is Saltersford Lock on the River Weaver

Caen Hill Locks... one of the longest flights in the country, at Devizes on the Kennet and Avon Canal

If a steep change in level is to be overcome a staircase lock may be used. A staircase lock is where one lock chamber is connected to another by a set of gates without a stretch of water or pound separating them. Operation of these staircase locks is more complicated than that of a single lock and in many locations navigation of these locks is overseen by a lock keeper or Canal and River Trust Volunteer. The sequence for operating a single pound lock is as follows...

Going uphill... when approaching a lock establish if the lock is full or empty and if there are any boats approaching the lock from the opposite direction. If the lock is full and a boat is approaching from the opposite direction it is common courtesy and a water saving procedure to allow the on-coming boat priority. When in this position I usually open the top gates for the approaching boat allowing them the luxury of cruising straight into the lock. If there are children on board the boat they can be possessive about who operates the lock so it is always wise to ask if they would like help operating the lock. Also, when opening paddles for other boats ensure that they are well clear of the cill (the ledge at the top of the lock that the gate sits on) and that they are ready for the paddles to be opened. Some boaters prefer to have the boat held in position by a rope when in a lock, especially if it is a wide lock. Ultimately, it is their choice and remember... not everyone has the same level of confidence, experience or expertise operating locks.

If the lock is full and there are no boats approaching, check that the top gates and paddles are closed before proceeding. Open the bottom paddles (as in the plughole on a bath) to empty the lock chamber. They are usually but not exclusively, mounted on or adjacent to the bottom gates, to empty the lock chamber. The paddles are usually opened by winding a rack and pinion arrangement with a windlass (or lock handle) although some may be hydraulically operated by using a windlass in the same way. Some waterways, like certain sections of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal have a different type of paddle known as a "clough". This consists of a handle adjacent to the side of the chamber that is lifted in a swivelling action to open the paddle. Also on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal will be found box paddles where the windlass is attached to a peg on the top of the unit for opening and closing. Another variation on some waterways is that instead of using a windlass, a handspike is used to raise the rack connected to the paddle. In built-up areas a handcuff key may be required to prevent unauthorised use of the paddles.

A single size lock windlass that will fit most lock paddle gear

A double size lock windlass that should fit all paddle gear

A typical Leeds and Liverpool Canal clough closed...

...and opened

An unusual box paddle on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal... the windlass is attached to the peg on the top

A handcuff type Anti Vandal Key

Before commencing winding the paddle, ensure that the safety catch, pawl, ratchet or wedge on a chain is engaged, that the handcuff lock (if fitted) has been unlocked and that the boat's steerer is ready. Once in the fully open position remove the windlass and wait for the water level to equalize with that of the pound below the lock. If the channel below the lock is restricted or narrow it is always advisable to keep the boat well back in the channel to avoid the wash from the by-pass weirs or turbulence from opened paddles. If this is not possible, temporarily tie the boat to a mooring bollard to prevent it being swept away by the flush of water from the paddles. If there are no bollards available try standing on the rope to save experiencing rope burns to the hands. When the water levels are approaching equalization the turbulence on the outside of the gates diminishes and the gates will move slightly indicating that they are nearly ready to be opened. There is a right and a wrong way to open the gates. The easiest way is to lean one's back against it and push backwards. Once the gate starts to move greater pressure can be exerted to open them fully. When steering the boat into the lock it is better if the chamber is approached from a distance rather than immediately below. This is because the boat needs space to manoeuvre. Once the bow is lined-up the stern can be brought around using the tiller or rubber and the chamber entered in a straight line. When the stern of the boat has cleared the gates they, as well as the paddles, can be closed. It is best to position the boat two thirds up the chamber although some steerers prefer to be right up against the vertical part of the cill. This is essential with longer boats but with shorter ones it will subject the boat to the turbulence from the water when the paddles are opened. If the boat is stopped two thirds of the way along the chamber the theory is that when the top paddles are opened the rush of water will start to push the boat backwards and when the water bounces of the bottom gates it will act as a brake preventing the boat from banging into the gates. Once the boat is in the correct position and a rope attached to the bollard (if required) the bottom gates are closed and the top paddles opened. If there is a combination of ground and gate paddles open the ground paddles half-way to prevent the surge of water creating too much turbulence and risking damaging the boat. As the boat rises in the lock it is essential to keep an eye on it in case it catches on any protrusions sticking out from the side of the lock chamber which may lead to the boat sinking. Once the water level clears the cill the paddle can be wound up fully provided that the boat's steerer is confident with it. The gate paddles should not be opened until the water level covers the apertures, again to prevent too much turbulence moving and possibly damaging the boat. As the boat rises up in the lock chamber ensure that the rope (if being used) is kept taught to prevent excessive movement and remove the possibility of it becoming wrapped around the boat's propeller. Once the water level has equalized with the upper pound's level the gates can be opened and the boat steered out of the lock. A little time saving tip is to wind the paddles down whilst the boat is exiting the lock chamber. I always try to lower any gate paddles before the boat reaches the gate to prevent any oil or grease being rubbed onto it and hence onto your hands. If one gets into the routine of doing this at this time on every lock it reduces the possibility of paddles being left up for subsequent users of the lock to close (if noticed). Once the boat has cleared the gate it can be closed and a quick visual check that all paddles have been closed.

If going downhill the same rules and procedures apply but with a few differences. If the lock is empty or partially full and there are no boats approaching, fill the chamber by using the top paddles. Once the water levels have equalized the gates can be opened, the paddles closed and the boat can enter the lock chamber. Once the boat is in the chamber the gate can be closed. Ensure that the boat is positioned well away from the cill to prevent the stern getting caught on it which can, as with going uphill, lead to the boat sinking. Opening the bottom paddles fully is not as problematic as opening the top paddles when there is a boat in the lock chamber. Once the water levels have equalized the bottom gates can be opened and the boat can leave the lock. As with going uphill, close the paddles whilst the boat is leaving the lock and close the gates when it is clear unless there is a boat waiting to enter the lock. If this is the case it is always good canal etiquette to close the gates after the boat waiting has entered the lock before leaving.

With broad locks do not be afraid to share the lock with another boat or, if on a narrow canal, share a lock with a boat of a suitable length. When sharing a lock with another boat there is less space for boats to be affected by water turbulence although some owners do not like sharing as the competence of the steerer of the second boat is unknown. Staircase locks have their own set of problems and instructions can vary depending upon the number of chambers. But certain rules apply to all staircase locks. When going uphill ensure that the bottom chamber is empty and the upper chamber(s) are full and proceed as if using conventional locks without a pound between them. When going downhill ensure that the top chamber is full and the bottom chamber(s) are empty. As operating the lock proceeds, the reason for this will be appreciated. If the staircase locks are wide it is possible for boats going uphill to share with boats going downhill. This is known locally (in the Northwest waterways) as the "Bunbury Shuffle" if it is a two-step staircase or the "Northgate Shuffle" if it is a three-step staircase lock.

Boats doing the "Northgate Shuffle"

There are other numbers of chambers in staircase locks such as Bingley Five Rise on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal which, as its name suggests has five broad chambers and at Foxton on the Grand Union Canal where there are two narrow locks that possess five chambers. There is an excellent graphic representation of how locks operate on Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lock_(water_navigation). It is also worth noting that on many river navigations locks are operated electrically and sometimes attended by lock keepers.

There are other means of overcoming changes in height in the shape of boat lifts. There are currently two in operation on the British canal network, one is the Anderton Boat Lift at Anderton in Cheshire which is a vertical lift to overcome the 15-2 metre (50 feet) difference in levels between the Trent and Mersey Canal and the River Weaver. Boats are manoeuvred into caissons (or tanks) that are sealed with guillotine gates at either end and raised or lowered hydraulically.

The Anderton Boat Lift connects the Trent and Mersey Canal to the River Weaver

The other is the Falkirk Wheel which raises or lowers boats in caissons between two levels of the Forth and Clyde Canal with the Union Canal where a flight of locks previously overcame the 24 metre (79 feet) difference in levels but were lost when the canal was abandoned. Details of these unique structures can be found in the Wonders of the Waterways section of the Canalscape website along with many other canal features worthy of note that are featured.

The Falkirk Wheel on the Forth and Clyde Canal in Scotland

Buying a boat, like buying a car, can be a minefield, only more so. The Inland Waterways Association publishes a guide for prospective boat buyers that offers advice and guidance that is extremely useful and offers sound advice. There are many considerations that require thought and research when buying a boat. The most common over-riding factor is that of cost. If the budget is sufficient should a new or used boat be purchased? This something that only the purchaser can answer. Other defining factors are if the prospective owner wants (or can afford) a steel narrowboat, a wide-beam canal cruiser or a GRP cruiser. The canals and inland waterways that the prospective owner wishes to cruise on are also defining factors. For example: it is no good considering a wide-beam boat if the waterways it is to be based on can only accommodate narrow-beam craft. Similarly, it is not good buying a boat over sixty feet in length if the locks cannot accommodate boats of this length. For more information on various types of canal cruisers follow the link to the Don't Call It A Barge section of the Canalscape website. Some people buy a boat to live on and this opens-up a whole new can of worms. If this is something that you are considering contact the Residential Boat Owners Association who can provide a wealth of advice, knowledge and guidance on this subject.

Obviously, a new boat should not require any work unless a bare hull which is as its name suggests is the basic steelwork, that requires the mechanics, ballast, electrics, water tanks, plumbing as well as fitting out to be accomplished, is purchased. A sail-away is a hull with the mechanics, ballast, windows and doors, basic electrical wiring, water tank and plumbing fitted as well as exterior fittings, the floor and depending upon the supplier some bulkheads, leaving the majority of the fitting out to be completed by the owner. Another option is a project boat. That is, a used boat that requires refitting or other substantial work such as re-bottoming. If considering a boat such as this it is no good having a mooring that does not possess basic amenities such as water or electricity. The choice depends upon the budget and capabilities of the prospective owner. Other family members that will be using the boat also need to be consulted. It is no good buying a boat only to discover that your wife or partner doesn't like it or it is not suitable for children or the family pet!

A used boat has its own set of problems. These range from the condition of the hull, mechanics, fit-out, paint work, etc. Many of these items can be assessed by inspecting the current Boat Safety Certificate or by having an independent survey of the boat which will require the boat to be out of the water in order for the hull condition to be assessed. In some ways "you pay your money and take your chance!" Whatever you decide it is always advisable to take an experienced boat owner with you to give advice and guidance.

Once you have decided whether to buy new or used the main design criteria needs to be considered. This is similar in many ways to the considerations when hiring boat such as size, design, number of berths, layout, etc. It is an idea to make a list of your requirements and then scour the advertisements in the canal magazines or visit marinas that have brokerage services similar to when buying a car from a dealer. Again, take an experienced canal boat owner with you to give advice and guidance. As with buying a car, it is all to easy to fall in love with the first boat you see so don't fall into the trap of impulse purchasing. Ask around and speak to other boat owners and boat chandlers who may also know of suitable boats for sale.

Another consideration that many overlook is where to keep it. Marina moorings are secure, offer many facilities but can be expensive expensive. There are many locations where linear moorings (where boats are moored at the side of the canal) are offered but usually do not have the security and facilities offered by a marina. Boat clubs offer good moorings, but on some waterways, there may be a waiting list that can be as long as a year or more. You may also need to be a member of the club concerned to be considered for one of their moorings so it may be worthwhile becoming a member and waiting until a mooring becomes available. Most navigation authorities can give help as to where moorings are available in a particular area. They are listed in the Useful Links section below under the heading of Navigation Authorities.

Other financial considerations are the running costs such as mooring fees, canal licence, maintenance costs such as regular hull cleaning/painting/blacking/sacrificial anode replacement/Boat Safety Certificate work/engine maintenance/ exterior painting, etc. Don't forget, ask any boat owner and they will confirm that you can throw fifty pound notes at a boat, and they don't stick!

So there you have it... a quick guide as to how to get started canal cruising and some basic canal cruising information. This not a definitive guide to the subject but just an introduction. There are plenty of in-depth guides to navigation and the best way to hire or buy a boat. If considering hiring a boat, visit the hire companies and look around their boats. If thinking about buying a boat, do your homework and speak to other boat owners about the subject. If you are thinking about living on board a boat think long and hard and speak to others who already live aboard. It is not for everyone but whatever route you decide to go down just remember one thing... canal cruising is contagious and if you like it, once started and you are hooked, it is difficult to give up. I know and have nearly sixty years of boating experience to prove it! If you do decide to go canal cruising it is an enjoyable pass-time shared by many who want something different, a slower pace of life or just want to get away from it all. I don't care if you are in a town, city or in the countryside... as soon as you walk onto the towpath prepare to change down a couple of gears as you are entering a whole new world with, spectacular views, tons of history and heritage plus a more relaxed and slower pace of life!

An idyllic rural mooring above Baddiley Locks on the Llangollen Canal

Local (North West England) Day Hire and Hire Boat Companies

ABC Boat Hire - http://www.abcboathire.com

Andersen Boats - http://www.andersonboats.com

Anderton Marina (Hoseasons) - http://www.hoseasons.co.uk

Black Prince Boat Hire - https://www.black-prince.com

Bridgewater Boat Hire - http://www.bridgewatermarina.co.uk

Chas Hardern Narrowboats - http://www.chashardern.co.uk

Claymoore Narrowboats - http://www.claymoore.co.uk

Midway Boats - http://www.midwayboats.co.uk

Thorn Marine - http://www.thornmarine.co.uk

UK Canal Boating Hire Companies - http://www.ukcanalboating.com

This is just a selection of the more popular hire boat companies in the North West of England...

others can be found by typing "narrowboat hire" into Google or other search engines

Navigation Authority and Other Useful Websites

Most inland waterways are controlled by either the Canal and River Trust or the Environmental Agency

although some other canals and waterways may be controlled by independent navigation authorities

Association of Waterways Cruising Clubs (and FBCC) - http://awcc.org.uk

Boat Safety Scheme - http://www.boatsafetyscheme.org

Bridgewater Canal Company - http://www.bridgewatercanal.co.uk

Canal and River Trust - http://canalrivertrust.org.uk

Canal Boat Magazine - http://www.canalboat.co.uk/home

Environmental Agency - https://www.gov.uk

Inland Waterways Association - https://www.waterways.org.uk

Manchester Ship Canal Company - http://www.peel.co.uk

Residential Boat Owners Association - https://www.rboa.org.uk

River Weaver Website - http://weaver.britainswaterways.co.uk

Unlock Runcorn (Runcorn Locks Preservation Society) - http://www.unlockruncorn.org

Waterways World Magazine - http://www.waterwaysworld.com

Useful Commercial Contacts

AKT Solar Panels - http://www.aktsolar.co.uk

All Seasons Boat Covers - http://www.allseasonscovers.co.uk

Apollo Duck (boat sales) - http://www.apolloduck.co.uk

Aquafax Engineering - http://www.aquafax.co.uk

CabinCare (side door & hatch fly screens & blinds) - http://www.cabincare.co.uk

Canal Warehouse - http://www.canal-warehouse.co.uk

Craftmaster Paints - http://www.craftmasterpaints.co.uk

Crowther Marine (stern gear) - http://www.crowthermarine.co.uk

Goodwin Plastics (custom made water tanks, shower trays, etc) - http://goodwinplastics.co.uk

Hesford Marine - http://www.hesfordmarine.com

International Paints - http://www.boatpaint.co.uk

Longford Canal Services - http://www.longfordcanalservices.co.uk

Midland Chandlers - http://www.midlandchandlers.co.uk

Miracle Leisure Products - http://www.miracleleisureproducts.co.uk

Nantwich Canal Centre (Nantwich Marina) - http://www.nantwichmarina.co.uk

Uplands Marina - http://www.uplandsmarina.co.uk

Narrowboat Paints - http://www.narrowboatcolours.co.uk

New Blinds (side door fly screens & blinds) - http://www.newblinds.co.uk

River Canal Rescue (emergency services) - http://www.rivercanalrescue.co.uk

Rylard Paints - http://www.rylardboats.com

Seals Direct (window seals, etc) - http://www.sealsdirect.co.uk

Stretford Marine Services (Stretford Marina) - http://www.stretfordmarine.com

Thorn Marine - http://www.thornmarine.co.uk

Text

|

|

"Canalscape" and "Diarama" names and logo are copyright |

Updated 28/10/2018